Why European Life Science’s Momentum May Finally Become Unstoppable

Living in Europe and watching the scene firsthand, it seems biotech here doesn’t revolve around a single gravitational center. There’s no Kendall Square-kind of place here, no San Francisco–style mega-cluster anywhere on the map. Instead, Europe operates like a distributed constellation—a network of regional ecosystems that, while historically siloed, are becoming more connected, complementary, and strategically aligned than ever before…

A View From the Edge

It was a grey August afternoon in Riga, Latvia—more Baltic chill than biotech buzz. A short cab ride from the city’s quiet art nouveau boulevards took me to a less-traveled part of Europe’s life sciences landscape: the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis (LIOS).

You are not expecting a global life science hub here—and to be clear, it isn’t one. Latvia is not a country anyone would cite in the same breath as Switzerland, France, or Denmark when discussing European life sciences. I came not for scale, but for something else: a sense of what’s quietly brewing in less-known regions, where a few high-quality players might be early signals of a broader shift.

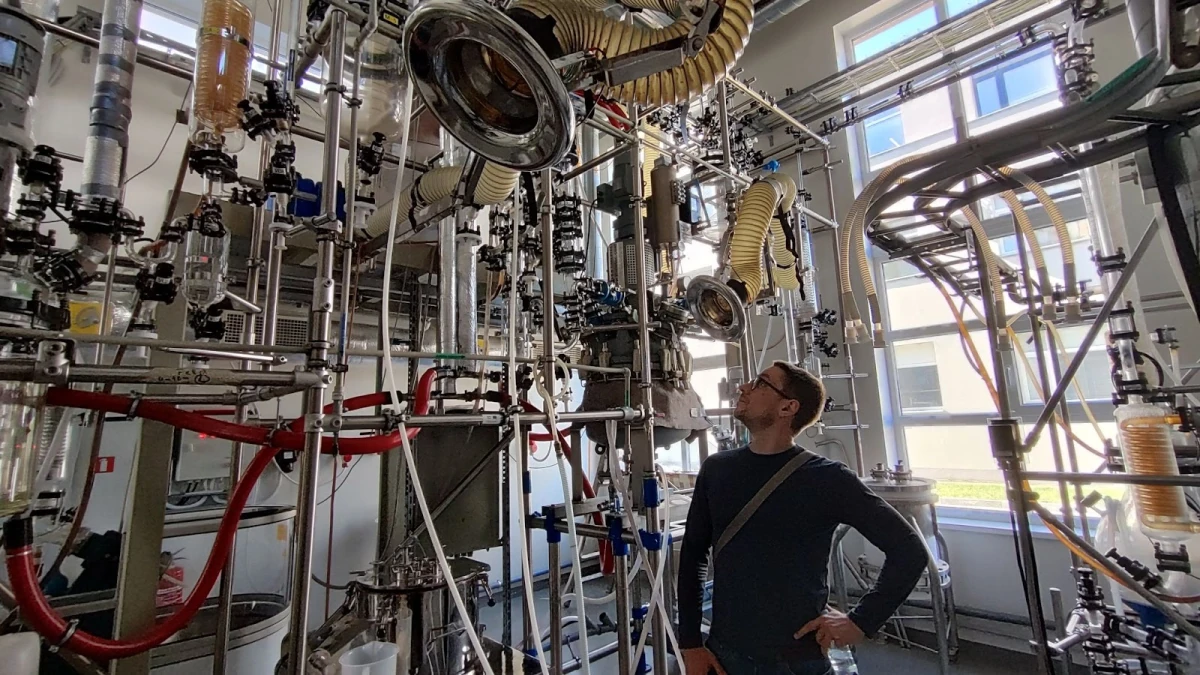

It was Andrii Lozoniuk, a member of the BiopharmaTrend advisory board and a sharp observer of Central and Eastern European life sciences, who brought me here. As someone deeply involved in connecting regional science with international biotech conversations, he has a knack for uncovering what's easy to overlook. “It’s not a biotech cluster,” he told me candidly as we walked through the LIOS building, “but it’s a place where you can do world-class drug discovery and biotech science at a fraction of the cost of major hubs like Boston.”

Andrii Buvailo, visiting Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis (LIOS), August 2025

What I saw, indeed, was a research institute with serious technical capabilities: full-spectrum drug discovery and development infrastructure, including vivarium and cutting analytical equipment, but above all, an experienced team that’s worked with both academic and commercial partners across Europe and globally.

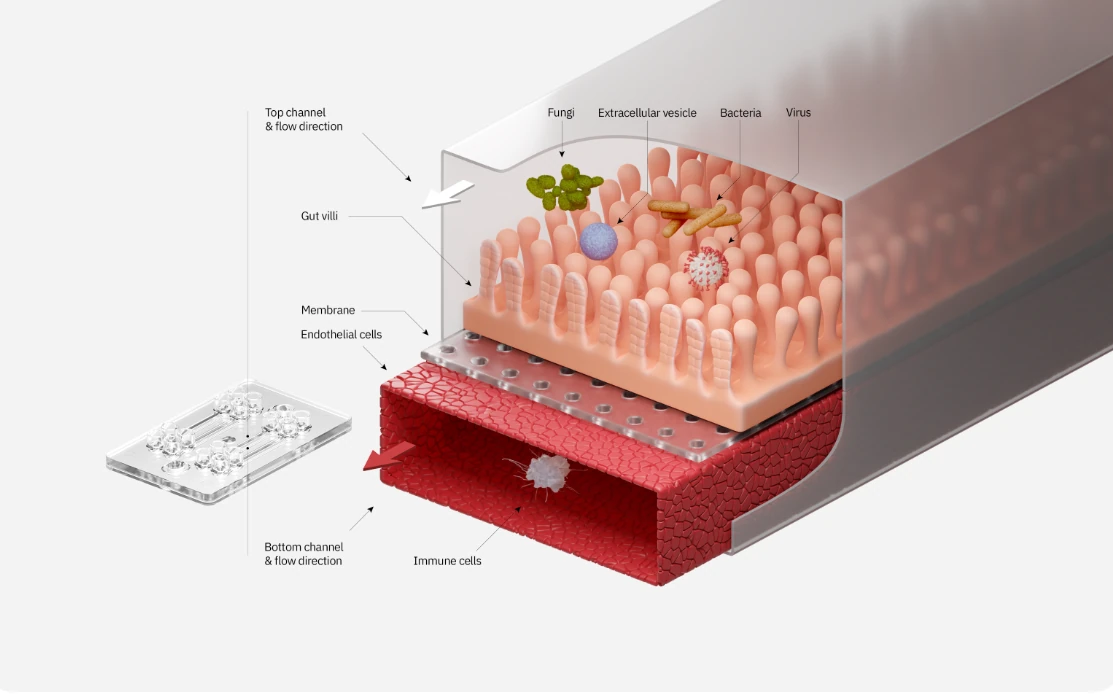

Among the standout examples of the Latvian life science startup scene was Cellbox Labs, a local biotech startup building organ-on-chip systems designed to replace animal testing with more predictive, human-relevant models. They recently secured €3.3 million in non-dilutive EU funding, a notable achievement not just for Latvia but for any young company navigating Europe’s fragmented funding landscape.

Their approach is deeply technical: scalable, chip-based platforms that incorporate oxygen and pH sensors, enable patient-derived cell inputs, and are being used to test drug responses in organ systems like the gut and pancreas. The company is even working on in vitro–in vivo translation models—digital twins that tie lab results to real-world human biology. In short, they’re solving problems that the global pharma industry is actively grappling with.

Cellbox Labs’s technology to substitute animal testing for drug discovery

Latvia is the second Eastern European country that I visited lately, with an idea of uncovering local life science gems. Back in 2023, I traveled to Lithuania to cover the Life Sciences Baltics 2023 event, and I was quite impressed with what I saw. Cities like Vilnius and Kaunas are home to a growing number of biotech and deeptech startups, many of them bridging biology with artificial intelligence, microfluidics, and synthetic biology. Lithuania, according to its own Innovation Agency, is among the fastest-growing life sciences economies in Europe, already contributing nearly 3% to national GDP—a remarkable figure for a country of under 3 million people.

Related: How Lithuania's Deep Tech Ecosystem Is Fueling the Country's Life Sciences Boom

The legacy of protein manufacturing, traced back to Thermo Fisher’s acquisition of Fermentas in 2010, has created a unique talent pool that’s now producing startups like Caszyme, a local “star” with global ambitions, co-founded by CRISPR trailblazer Dr. Virginijus Šikšnys and Dr. Monika Paule, which is expanding the boundaries of genome engineering with a platform built on more than 90 distinct Cas9 orthologs. Other examples I saw were Biomatter, using generative AI and physics-based models to design bespoke enzymes and therapeutic proteins with atomic-level accuracy; Atrandi Biosciences, translating high-precision microfluidics into industrial-scale single-cell analysis; Delta Biosciences, fusing AI, DNA barcoding, and droplet microfluidics to compress drug-screening cycles from weeks to hours, and dozens more…

The accelerating shift in the life sciences is even more visible in some bigger nearby economies, like Poland or the Czech Republic... For instance, Polish Selvita and Ardigen, Ryvu Therapeutics, and Captor Therapeutics anchor a growing biotech and computational-drug-discovery ecosystem fueled by strong talent in the cities of Warsaw, Kraków, and Wrocław, among others.

The Czech Republic’s rise is driven by a deep structural biology and protein-science ecosystem built around the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC) and Biotechnology and Biomedicine Centre of the Academy of Sciences and Charles University (BIOCEV), complemented by growing spinout activity from Charles University and Masaryk University and the expansion of Prague and Brno as clinical-research and analytics hubs…

According to Jan Macek, CEO of Deep MedChem, a Prague-based AI-powered drug-discovery company that develops the “CHEESE” platform for ultra-fast molecular-space search, virtual screening, and predictive modeling, Czechia’s momentum is increasingly shaped by the Prague.bio cluster, which has in just a few years become the key coordinator linking academia, industry, biotech, and techbio spinouts, small companies, and a growing investor and angel network through initiatives such as the Prague Bio Conference.

As Andrii and I reflected on our visits to Central and Eastern European countries, we began to see them not as isolated chapters, but as early pages in a much larger European momentum…

The Capital Is Catching Up Across Europe… With Caveats

If you follow the startup money in biotech, you’ve historically been led away from Europe. For years, U.S. companies pulled in the lion’s share of venture capital, IPO proceeds, and late-stage financing. The European scene was often dismissed as cautious, undercapitalized, and fragmented—brilliant in science but uncertain in scale. That’s seemingly changing.

Among the recent signals of this shift is a surge of larger, more confident biotech raises, headlined by Germany-based Tubulis, which recently closed a €308 million Series C, a record for a still-private European biotech and the largest global raise ever for a private ADC (antibody–drug conjugate) company. The deal, led by Venrock Healthcare Capital Partners and joined by international names like Wellington Management and Ascenta Capital, is not just about capital; it reflects growing global confidence in European technical platforms. Tubulis' linker-payload technology enables precise, stable ADCs with reduced off-target toxicity, and is being developed against cancers like ovarian and lung. It’s high-end, IP-driven science built and backed in Europe.

Just a few weeks later, Medicxi, one of the continent’s most active life sciences investors, closed a €500 million fund, its sixth in a decade. The London- and Geneva-based firm has made its model clear: back asset-centric companies with clear product visions, often across borders and stages. Recent exits like Sanofi’s $1.15B acquisition of RSV startup Vicebio and Lilly’s acquisition of Versanis Bio have returned over a billion dollars to the fund, and Medicxi’s continued success suggests that mature, return-generating biotech investing is no longer confined to the U.S.

Around the same time, Paris, London, and Milan-based Sofinnova Partners closed Capital XI at €650M, above its €500M target and €600M cap. The fund will focus on seed and Series A biotech and medtech companies, with areas like oncology, immunology, CNS, and cardio-metabolic diseases. Some of the recent investments include HAYA Therapeutics (RNA platform for cardiometabolic disease) and Galvanize (pulsed electric field for solid tumors).

Angelini Ventures and the European Investment Bank are jointly committing €150 million to boost European early-stage life science companies. Each is putting in €75 million to co-invest in 7–10 biotech, medtech, and digital health startups across Europe. The new capital expands Angelini’s existing European footprint, including its role in Adcytherix’s €105M Series A, with a follow-on round now in preparation as the French ADC developer readies multiregional clinical-trial filings for ADCX-020. Angelini’s recent deals also include financing NUCLIDIUM’s CHF 79M raise for Phase IIa radioligand programs

The maturation of capital also shows in who’s raising. In Belgium, firms like Forbion and Sofinnova are anchoring larger syndicates. Argenx, now Europe’s most valuable public biotech at $47B market cap, came out of the VIB ecosystem—Belgium’s flagship research institute known for spinning out globally competitive companies.

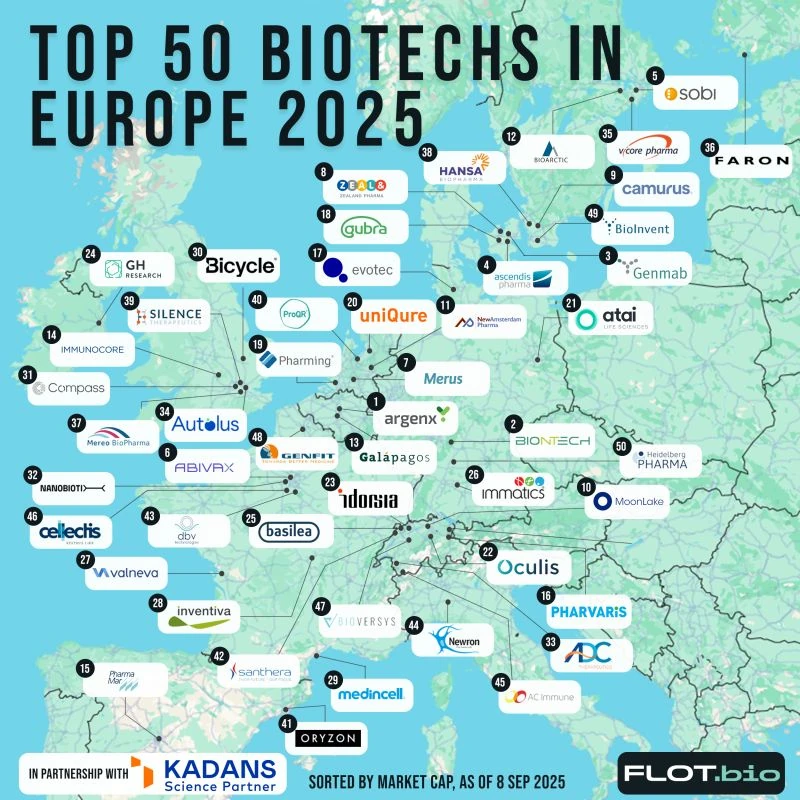

Berlin-based media and market research agency Flot.bio compiled an interactive map of the top 50 biggest biotechs in Europe, which shows a technologically diverse and geographically distributed life science community. “Europe’s biotech scale is bigger than I expected,” says Philip Hemme, Founder and CEO of Flot.bio and former co-founder and CEO of Labiotech.

Published with permission, credit: Philip Hemme/Flot.bio

At BIO International Convention 2025 in Boston, European VCs like Matthew Foy (Avante Biocapital) and Christina Takke (V-Bio Ventures) echoed the same refrain: Europe now has the capital, but more importantly, it’s learning how to structure companies to use it. One common challenge has been legacy governance—companies with outdated board structures, or early choices that didn’t anticipate international expansion or follow-on funding. That’s slowly being replaced by smarter planning from day one. This resonates with what Andrii Lozoniuk, learned during his visit to BIO-Europe 2025 in Vienna, in early November—one of the most important life science events in Europe that in 2025 brought together 5,900 life science professionals from over 3,200 companies across more than 60 countries.

Some founders, like the team behind Cradle in the Netherlands, are taking smart planning to the extreme. As Cradle’s co-founder and CEO, Stef van Grieken explains in his LinkedIn post, rather than “launching with a barebones Dutch BV”, they opted for a cross-border legal structure with Swiss-Dutch entities, clean equity lines, and an ESOP framework that works across the UK, US, and EU. The cost? Around €70,000 upfront. But it allowed them to raise a total of $100 million without legal rewrites, and with a cap table ready for a U.S. IPO or Delaware flip, if needed.

According to The Recursive, one of the heavily discussed ideas in the European Union these days is the proposed 28th Regime (EU-INC)—a voluntary, EU-wide corporate form designed to overcome the fragmentation that forces founders to navigate different corporate, labor, tax and compliance rules in every member state. Supporters argue it could finally offer one rulebook, one registry, fast digital incorporation, and seamless cross-border hiring, while opponents worry it may dilute national protections or reduce regulatory control, the report says.

With a formal proposal due in March 2026, the window to shape EU-INC’s final design remains open, but not for long.

Coming back to the European life science funding climate, it is a story of contrasts: despite Europe posting its strongest life-sciences fundraising quarter on record, this momentum is concentrated in a few mega-rounds while most early-stage companies continue to face a tight capital market. As U.S. public markets rebound—returning $40 billion to investors in a single month and reigniting IPOs and follow-ons—European firms remain closely tied to that liquidity to reset their own financing cycles.

Meanwhile, insights from BIO-Europe 2025 reported in PharmaPhorum highlighted how global development pathways, including collaborations in faster-moving clinical environments such as China, are increasingly seen as practical complements to Europe’s scientific strengths amid intensifying competition and a $90 billion pharma patent cliff.

The Talent Equation

If capital is the fuel of a biotech ecosystem, talent is its engine—and in Europe, that engine is quietly but steadily revving into higher gear. What Europe lacks in uniform speed or singular “mega-hubs”, it makes up for in something else: a continent-wide network of STEM excellence, high-quality academic institutions, and a growing class of scientifically trained professionals willing to move across borders in search of meaningful work.

It is evident across the entire European landscape. In Lithuania, for instance, over 56% of the population has a higher education degree, one of the highest rates in the EU, and around 25% of university students focus on STEM fields. The country reportedly supports around 15,000 researchers, with half working in life sciences.

While emerging life science hubs like Poland, the Czech Republic, and Lithuania are gaining momentum and finding their niches in the pan-European scene, established life science hubs, like Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Belgium, are traditionally spilling their influence both in terms of capital, job market, and source of talent.

In Belgium, for instance, academic institutions like KU Leuven, Ghent University, and Université libre de Bruxelles feed into one of Europe’s densest biotech labor markets. Training centers like ViTalent and aptaskil specialize in producing job-ready biomanufacturing and lab talent. Across the country, biotech jobs have grown 50% in a decade, and R&D investment has doubled to over €5 billion annually. There’s infrastructure here—scientific, political, and logistical—and investors are now leaning in. According to Essenscia reporting, the sector will require 1,500 new workers per year in Belgium over the next 3–5 years, and the infrastructure is already in place to supply them.

Denmark’s Medicon Valley, centered around Copenhagen and Southern Sweden, is another labor engine. With Novo Nordisk’s explosive growth in one of the most important pharmaceutical categories, GLP-1 drugs, sales representing 8.3% of Denmark’s GDP in 2023 alone—the gravitational pull of biotech in the region is immense. But the ecosystem doesn’t just lean on Novo. Companies like Genmab, Lundbeck, and Coloplast have built strong R&D pipelines, supported by a regional education system that emphasizes interdisciplinary science, regulatory training, and bioengineering.

In a global competition for life science talent, and STEM talent in general, Europe offers a combination of high living standards, safety, public services, and family support infrastructure that makes long-term employment more attractive—especially in contrast to the high-cost, high-pressure environments found in other, perhaps more financially attractive areas of the world. While salaries may be substantially lower in Europe than in Boston or San Francisco, for example—childcare, healthcare, housing stability, and social protections certainly add appeal to tip the balance for scientists considering where to settle.

This advantage becomes more meaningful in light of ongoing global political uncertainty. With visa regimes tightening and R&D funding becoming a bit of a “political football”, Europe’s relative stability could prove a draw for mobile researchers and operators. It may already be happening quietly, particularly among early-career postdocs and tech transfer professionals, some of whom may be choosing France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, the Netherlands, or Estonia over the traditional overseas destinations.

Afterthought: Changing Priorities

As the world, by and large, grapples with rising taxes and tax system complexity, tightening regulatory regimes, and increasing political volatility, Europe’s long-criticized structural frictions are beginning to look “less exceptional” and prohibitive by comparison. At the same time, Europe’s long-shaped unique advantages—dense scientific talent (especially STEM), globally competitive research institutes, stable and exceptionally developed public infrastructures, high living standards, especially in childcare, and relatively accessible medicine—are becoming more visible and more attractive to international founders, researchers, and investors recalibrating their sense of global opportunity and risk.

Europe may not be the easiest place to find capital and scale a life science venture. But it is increasingly one of the most sustainable environments to build one—long term.